Closing the gaps in Dementia diagnosis - the CONGA trial

- 17 September 2024

- 5 min read

The current diagnosis process for dementia is slow and can yield unclear results – often delaying access to treatment or keeping patients stuck in the diagnosis pathway.

A new study hopes to improve the diagnostic process, providing more accurate evidence for clinicians and helping patients to get appropriate treatment quickly.

Angus Prosser told us more about the CONGA trial.

The Dilemma for Dementia Diagnosis

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia. The disease progressively worsens over time, and can affect memory, problem solving, concentration, language and sometimes behaviour. It’s thought to be caused by abnormal protein changes in the brain, leading to the death of neurons, but there’s still research exploring the exact pathway for what causes the disease. It’s immensely complex.

Before someone is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, they’re often given a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). This is when someone has problems with their thinking, worse than what would be expected as part of normal ageing, but not so bad it affects their daily living. The difficulty is that not everyone with these symptoms progresses to a form of dementia. In the early stages, symptoms can also be subtle, and individuals can present differently. As you can imagine, this makes it really difficult to diagnose someone – people can present with the same symptoms for many different conditions.

Currently, it can take years for someone to get a clinical diagnosis for Alzheimer’s disease. And there’s a significant diagnostic gap, where 30-40% of people with Alzheimer’s don’t have a diagnosis.

But a diagnosis is critical for care planning. And studies show that early diagnosis improves patients, and carers, quality of life and outcomes – reducing the likelihood of hospitalisation and delaying hospice care.

Identifying Alzheimer’s at an early stage is becoming even more critical with the emergence of new treatments for Alzheimer’s. Studies have shown that targeting a specific protein in the brain called amyloid can slow the progression of the disease, giving people more time to live well with Alzheimer’s.

These treatments have been shown to be most effective for those early in the disease, highlighting the importance of identifying and treating Alzheimer’s early. More accurate and earlier diagnosis would allow people to be offered clinical trials earlier in the disease progression and ensure appropriate care plans are in place.

It could also help us to be more confident about identifying patients that don’t have dementia, relieving patient and family anxiety and stress that is often present before they are given the all clear.

Making diagnosis easier and earlier - the CONGA trial

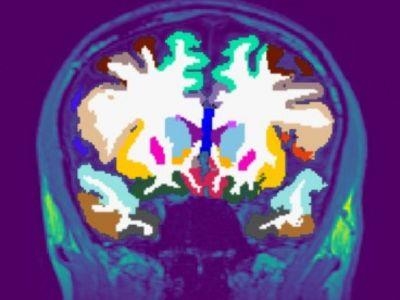

Around four years ago we were approached by Oxford Brain Diagnostics (OBD), a company that has developed a new technique to analyse normal MRI brain scans, called Cortical Disarray Measurement (CDM). It’s a technique that can identify microscopic changes in the brain which are thought to be linked to Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

CDM uses the same brain scans that are already used as part of dementia diagnosis, but a specialised sequence on the scanner which looks at the flow of water through the brain. This can provide information on tissue microstructure in the grey matter of the brain, and changes that are linked to potential underlying pathology.

Currently, an MRI scan is used clinically to look at basic structure of the brain to identify brain shrinkage. But gross volume loss in the brain is not seen until the later stages of the disease, so it often provides little information in the early Alzheimer’s and mild cognitive impairment stages. A more sensitive measure could help improve earlier detection and diagnosis.

Although OBD had promising preliminary data on the imaging technique, they needed to complete a larger scale analysis to see whether it could be effective in a real-world population. We developed the CONGA trial to see whether we can use this CDM technique to identify changes associated with Alzheimer’s earlier than what’s currently available.

We’re also working with the University of Oxford who are completing patient interviews and health economics in the CONGA trial to find out how the CDM technology could impact the NHS dementia diagnostic process and patients’ dementia journey. The CONGA study is recruiting until the end of October 2024 and currently we have 85 people enrolled – our target is to recruit 200 participants. Recruitment is completed at three sites: University Hospital Southampton, Dorset University Healthcare and Cardiff and Vale University Health Board. We’re working with the CRN to approach GP surgeries to screen participants at Primary Care level and we’ve added Patient Identification Centres to also help us with recruitment.

Ultimately, we want to know if we can use the CDM technique to improve the accuracy and the timeliness of dementia diagnosis and whether we can use it to identify individuals who are more likely to progress from MCI to Alzheimer’s, compared to current methods.

Collaborating for success

This study has had to be collaborative for us to succeed. We worked closely with OBD, the University of Oxford, and Cardiff University, and were awarded an NIHR i4i Product Development Award to further develop the CDM technology and gather larger scale data to prove its effectiveness. Professor Christopher Kipps, Clinical Director of Research & Development in Southampton & Professor of Clinical Neurology and Dementia, and I led on the development of the CONGA study to clinically validate this technology.

In addition to the main partners in the grant application, we’ve connected to Bournemouth University’s Institute of Medical Imaging and Visualisation, and The Healthshare Clinic Winchester, who joined the study to increase our scanning capacity.

Collaborating for recruitment has also been important. Identifying early-stage patients who are willing and able to take part can take time. To help with recruitment, we work closely with regional memory clinics and imaging services to make sure patients are aware of the study. We’ve also made new connections with Dorset Healthcare University to help recruitment, and worked closely with the CRN Wessex to provide additional staff for supporting the delivery of the project, to promote the study, and to link to primary care sites.

Although it has been challenging at times to make these connections, the network we have created has strengthened the project and provides a strong base for future collaboration. It has however been a steep learning curve.

It’s also important to note that we have strong Patient and Public Involvement in developing everything from the study protocol and patient information sheets, to how we structure the study, approach participants, and determine how much is appropriate to ask participants to do at the study visits. We have quarterly steering group meetings with patient representatives to move the trial on and help direct us.

Working collaboratively has been so important. Having lots of partners adds different perspectives and expertise, which opens up our eyes to different approaches. It’s not just about answering the questions we have, but paving the way for future trials, and learning to make the process as good an experience for participants as it can be.